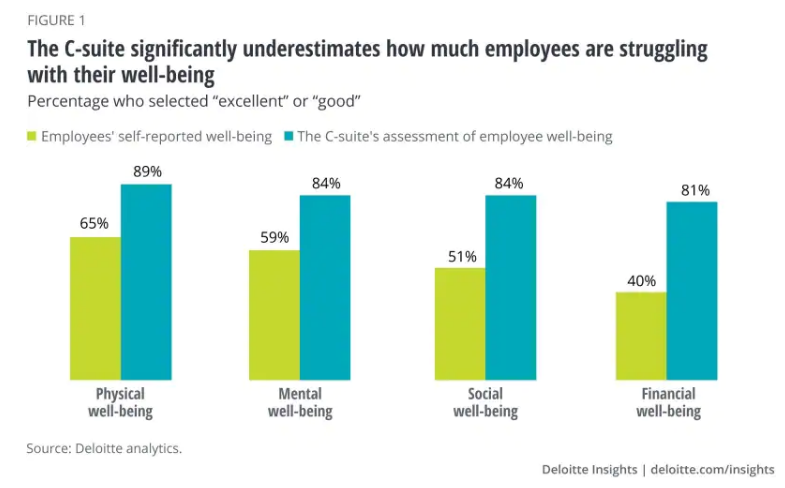

En este informe de Deloitte aparecen datos que quizás podrían parecer preocupantes (aun no tengo muy clara cuál es la diferencia de muestra y metodología entre el “self-reported” y “C-suite”)

Casualmente tengo algunos archivos de datos que me permitirían comprobar si a mí me salen unas cifras parecidas. Es una de las cosas que me gustaría hacer al regreso de las vacaciones, si a mis estudiantes les interesa conocer el dato (o en redes sociales me contáis que podría ser algo interesante).

Supongo que sería interesante no solo conocer los niveles de bienestar, sino las palancas que ayudan a tenerlo o las barreras que lo reducen.

Hace un par de años publicamos Changes in the Association between European Workers’ Employment Conditions and Employee Well-Being in 2005, 2010 and 2015 (Marin-Garcia JA, Bonavia T, Losilla J-M. Changes in the Association between European Workers’ Employment Conditions and Employee Well-Being in 2005, 2010 and 2015. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(3):1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031048 ).

En ese trabajo analizábamos como afectaban determinadas condiciones de trabajo al “mental well-being” con los datos disponibles hasta el momento.

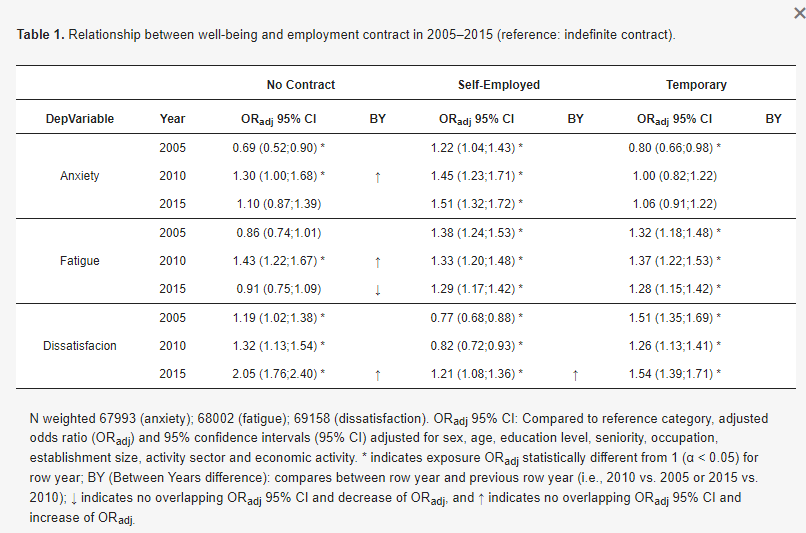

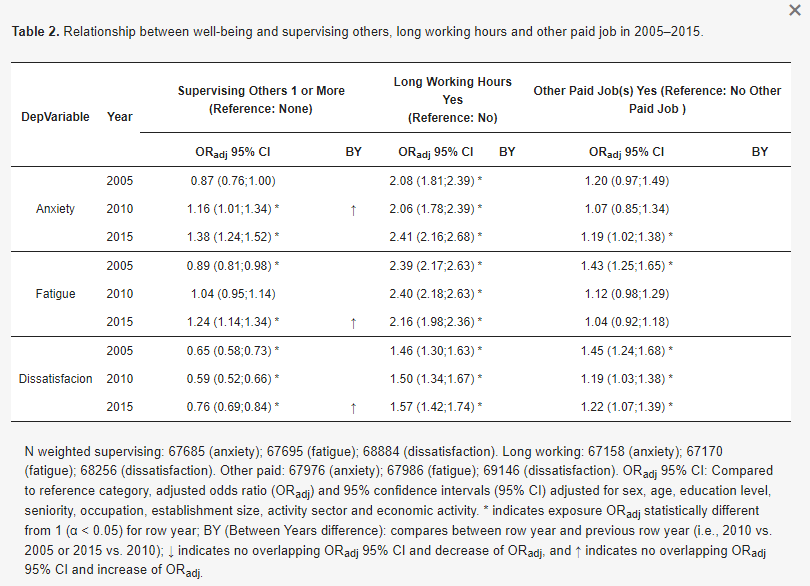

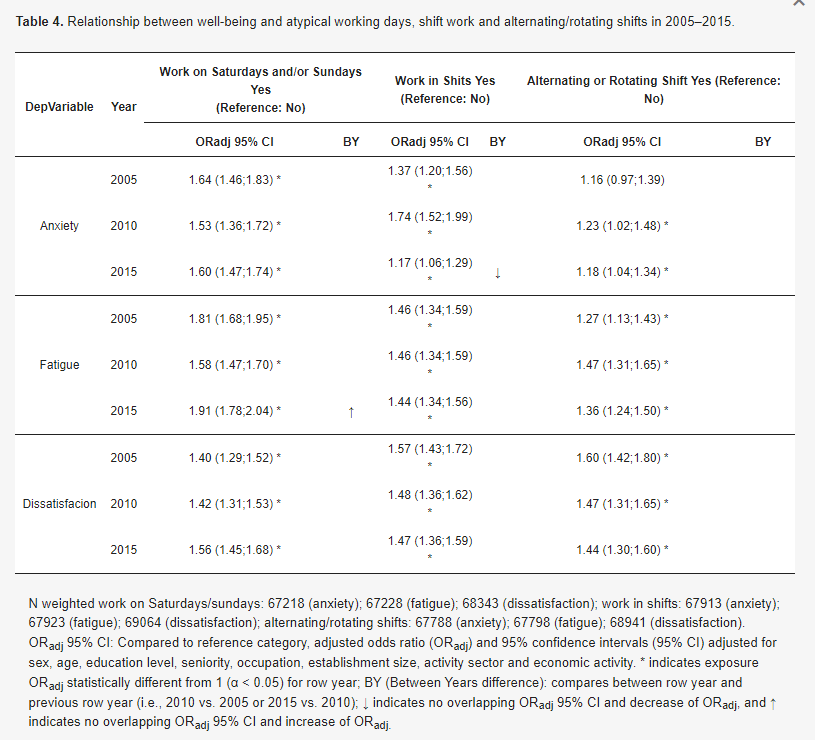

In general terms, and with the same situation for the adjustment variables (gender, age, level of education, seniority, occupation, establishment size, activity sector and economic activity), the people with indefinite contracts, no supervising responsibilities, who work between 36 and less than 45 h/week, do not work long working hours, do not have several jobs, do not work shifts (neither set nor alternating/rotating shifts) and do not work weekends report less anxiety, fatigue or job dissatisfaction than those in any of the other categories of each employment condition herein analyzed. That is, worse employment conditions lead to higher odds of suffering anxiety, fatigue or dissatisfaction compared to the reference category. Nonetheless, we observed that this relation did not always appear in this way for all the studied years for some working conditions (employment contracts other than indefinite contracts, supervising others and weekly working hours)

Para quien quiera “bucear” en los detalles, estas son las tablas de resultados. Son un poco complejas de entender para quien no esté acostumbrado a los “odds ratios”. Las cifras de la tabla comparan una opción de condición de trabajo (el encabezado de las columnas) con otra que se considera de referencia y nos indican la como aumenta (si el valor es mayor que 1) o disminuye (si es menor que 1) la probabilidad de sufrir uno de los síntomas (ansiedad, fatiga o insatisfacción).

Odds Ratio: the odds of having the target disorder in the observed group relative to the odds in favor of having the target disorder in the reference category group

Asi, por ejemplo, en la tabla 1, que compara tipos de contratos, las personas sin contrato, en el año 2015, tenían el doble de probabilidad de experimentar insatisfacción que las que tenían contrato indefinido. O, en la tabla 2, las personas que ocupaban puestos de supervisión, en el año 2015 tenían más probabilidad de sufrir ansiedad que las que personas que no supervisan el trabajo de otras (un valor 1,38 veces la probabilidad de las que no supervisaban). Curiosamente en el año 2005, la probabilidad para ese grupo era el 0,87 (es decir, menor) de la probabilidad de ansiedad en las que no supervisaban. Supervisar a otras personas generaba menos ansiedad en 2005 que en 2015, también generaba menos fatiga en 2005, mientras que en 2015 generaba más fatiga. Sin embargo supervisar a otras personas parece ser un factor protector contra la insatisfacción (están menos insatisfechos los que supervisan a otras personas) y se ha mantenido en los mismos niveles durante la serie de años estudiados.

Visitas: 17